Master thesis research with Femme International

Between September and December 2017, I have conducted research alongside Femme International to collect qualitative data for my M.Sc. thesis in Human Security at Aarhus University in Denmark. In June 2018, I have finally handed it in and gave it the title “The monthly costs of bleeding – An exploratory study on the connection of menstrual health management, taboos and financial practices amongst schoolgirls in the Kilimanjaro region in Northern Tanzania”.

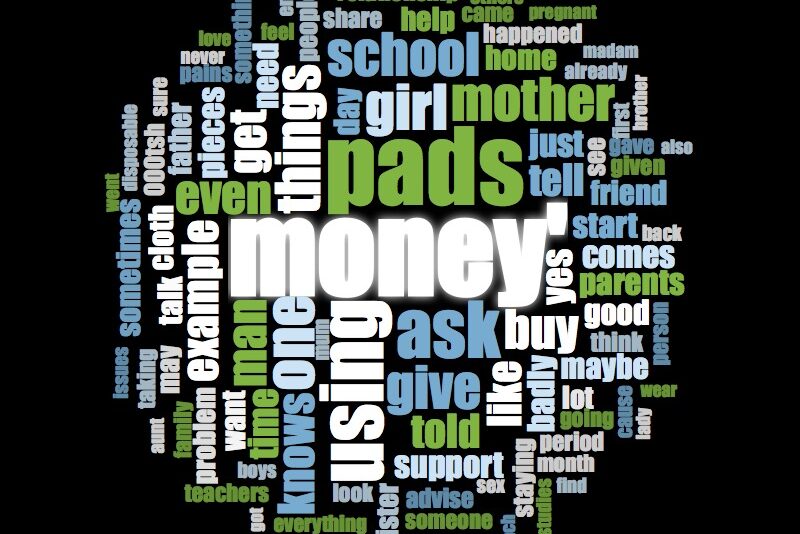

My interest in this field originated in the desire to understand the practice commonly described as “sex for pads” that I came across when I started to explore the connection between menstrual health and human security. Since I initially assumed this practice was a consequence of financial struggles, I started my research with a focus on the connection between MHM and financial insecurity. During my three months with Femmein Moshi, however, I realised that engaging in transactional sex or relationships is not exclusively a result of financial needs, but also connected to cultural practices, power and social structures within the respective societies. Just like most (reproductive) health behaviours, MHM is embedded in larger structures.

To understand the girls’ experiences, their voices and perspectives are central. I have gathered qualitative data to analyse various strategies that schoolgirls use to obtain MHM products or money to buy products. The main strategies I have encountered are support from family, teachers or school staff, friends and community members, work and engaging in transactional sexual relationships. Whilst these strategies all show a degree of agency, I am exploring the inhibitions through social structures and show the damaging consequences some of the girls’ methods can have. Additionally, their decision-making power is impacted by their identity, position in society and education system, other people’s expectations, and a variety of menstrual taboos.

The goal of my thesis is to illustrate the complexity and interconnectedness between MHM, reproductive and sexual health, financial insecurity, and underlying societal structures and cultural perceptions and practices. I am showing that attempts to improve MHM practices exclusively in relation to financial struggles or inaccessibility of menstrual products will fall short when underlying structures are ignored. Further, I argue that the pervasiveness of patriarchal structures entangled in Tanzanian society, the financial and economic disadvantages and the taboo of menstruation are forms of structural violence against women. They result in MHM practices that put women and girls at higher risk in terms of assault, direct violence and health problems.

For anyone interested in reading more, you can read and download the whole thesis here.

Katja Brama

From experience, I have learned to give a brief definition of my field before elaborating why it is relevant in any context. The general ideas of Human Security have been around for a while but as a concept, it was made popular by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 1994. Its two main aspects are ‘freedom from want’ and ‘freedom from fear’ and the UNDP defines its purpose as ensuring that ‘people can exercise choices safely and freely – and that they can be relatively confident that the opportunities they have today are not totally lost tomorrow.’ It is an approach that focused on the individual rather than the nation state and consists of seven security dimensions that are all interconnected: Economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political security. In an ideal – and unfortunately rather utopian – world, a balance of these dimensions would lead to a peaceful, stable and safe existence of all people and societies.

From experience, I have learned to give a brief definition of my field before elaborating why it is relevant in any context. The general ideas of Human Security have been around for a while but as a concept, it was made popular by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 1994. Its two main aspects are ‘freedom from want’ and ‘freedom from fear’ and the UNDP defines its purpose as ensuring that ‘people can exercise choices safely and freely – and that they can be relatively confident that the opportunities they have today are not totally lost tomorrow.’ It is an approach that focused on the individual rather than the nation state and consists of seven security dimensions that are all interconnected: Economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community and political security. In an ideal – and unfortunately rather utopian – world, a balance of these dimensions would lead to a peaceful, stable and safe existence of all people and societies.